By Sharon Oliver, Contributing Writer

CAMBRIDGE – Born into a wealthy family in Peking (Beijing) China in 1917, Joyce Chen grew up in a household with a family chef who later left to cook for her father’s friend. This left her mother and governess in charge of cooking every meal, all under the watchful eye of a young Joyce. By 1949, Chen, along with her husband Thomas and their children, left China and settled in Cambridge.

First restaurant

Harvard and MIT students craving authentic Chinese food prompted Chen to open her first restaurant, Joyce Chen Restaurant in Cambridge in 1958. A bilingual menu of American and Chinese dishes attracted Asians and notable Americans like Harvard president Nathan Pusey and President Eisenhower’s cardiologist, Paul Dudley White. According to her son, it is Chen who introduced the all-you-can-eat Chinese dinner buffet, which was a sales boost idea for those often-slow Tuesday and Wednesday evenings. She also taught cooking lessons in the early 1960s at the Cambridge Adult Education Center. Her classes were so legendary there were waiting lists to enroll.

Cambridge’s new chef believed in healthy Chinese cooking and did not use artificial dyes or other food coloring and used healthier ingredients like canola oil. She introduced northern Chinese (Mandarin) and Shanghainese dishes like Peking duck, hot and sour soup, potstickers, scallion pancakes and moo shu pork to Boston. After her divorce in 1966, Chen sold the restaurant to her ex-husband, who converted it to a Japanese restaurant called Osaka in 1972.

Photo/Pixabay

In 1967, she opened a second restaurant in a retail and industrial area near the NECCO (New England Confectionary Company) factory called The Joyce Chen Small Eating Place. Although the eatery seated 60 diners, people still lined up for Chen’s Chinese food. According to Chen’s son, Stephen, it was at this restaurant where his mother introduced the Northern style of dim sum (savory dumplings). Renowned chef and fan Julia Child was another regular at Chen’s restaurant.

Cooking show debut

That same year, Chen landed her own cooking show, “Joyce Chen Cooks,” on National Educational Television (NET), now known as Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). Making history as one of the first non-Caucasians to host a cooking show, Chen’s program filmed 26 episodes and reached audiences throughout the U.S., U.K., and Australia.

During the 1960s, the popular chef self-published her first cookbook after a publisher refused to include full-color images of her recipes. The strategy resulted in over 6000 copies of “Joyce Chen Cook Book” being sold to her restaurant customers before it even got to the printer. Aside from recipes, Chen included tutorials on the basics of cooking rice, eating with chopsticks, and making and serving tea. The cookbook sold over 70,000 copies and was reprinted many times over.

A successful restaurateur, television cooking show host and cookbook author, Chen branched out even further by launching a company called Joyce Chen Products, which included Chinese utensils, cookware and a patented crafted flat-bottomed wok with a handle, called the “Peking Wok” in the early 1970s. Her wok is still as popular today for its ability to retain and spread heat evenly.

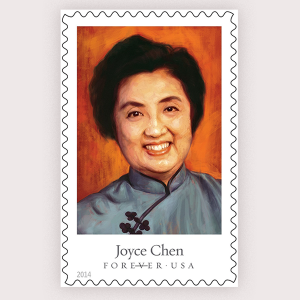

Immortalized on a stamp

In 2014, Chen joined an illustrious group of other culinary legends—James Beard, Julia Child, Edna Lewis, and Felipe Rojas-Lombardi—when the U.S. Postal Service immortalized their portraits with their “Celebrity Chefs Forever” stamp series. The stamps were unveiled at an event in Chicago. But Cambridge’s mayor David Maher, and postmaster Katherine Lydon held another reception to honor Cantabrigians Joyce Chen and Julia Child on October 29, 2014. A picture book about her life, “Dumpling Dreams: How Joyce Chen Brought the Dumpling from Beijing to Cambridge” was published in 2017.

Joyce Chen died in 1994 after being diagnosed with dementia.

RELATED CONTENT:

After more than 50 years, Grendel’s Den is still going strong (fiftyplusadvocate.com)

Necco’s sweet journey of creating classic candies began in Boston (fiftyplusadvocate.com)

Somerville nightclub Johnny D’s was a second home to many (fiftyplusadvocate.com)