Worcester was the longtime home of Major Taylor

By Jane Keller Gordon, Assistant Editor

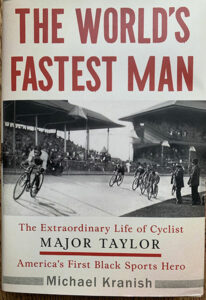

WORCESTER – There is a bronze statue of Major (Marshall) Taylor at the south entrance of the Worcester Public Library. Not far away, cars drive along Major Taylor Boulevard and park at the Major Taylor Parking Garage. Now, thanks to Michael Kranish, an investigative political reporter for the Washington Post and former writer for the Boston Globe, area residents will have a better understanding of Major Taylor’s life and accomplishments. Kranish’s book, “The World’s Fastest Man – The Extraordinary Life of Cyclist Major Taylor, America’s First Black Sports Hero,” has just been published.

Fittingly, Kranish launched his book tour at the Worcester JCC. In January, Lynne Tolman, a cyclist, editor at the Telegram and Gazette, and president of the Worcester-based Major Taylor Association, Inc., contacted Nancy Greenberg, cultural director at the Worcester JCC, about including Kranish’s book in the JCC Author Series.

“We had no idea that this would be the book’s launch,” Greenberg said. “We’ve had lots of publicity and have been very excited to welcome cyclists and our regulars.”

This past spring, Kranish spoke to the capacity crowd at the JCC.

“Eighteen years ago, I wrote a magazine article about Major Taylor that got a big response the weekend after 9/11… I wanted to write a book about his time, which was basically an era of apartheid in this country,” he said. “Four books later (Thomas Jefferson, John F. Kerry, Mitt Romney, Donald Trump), I wrote the book. It’s not the world’s fastest book but the book that I wanted to write.”

“There’s no film or video of Taylor. We can’t hear him talking. I think that’s why he’s not as well-known as other black athletes,” he added.

Kranish described Taylor’s story as a lens through which he explored racial injustice and one man’s ability to overcome insurmountable obstacles. Taylor was small black man — 5’7” and 140 pounds — competing against white men who were long-legged and bigger. The League of American Wheelman banned him from many races. He managed to become to fastest cyclist in the world, traveled abroad more than anyone at the time, according to Kranish, and achieved wealth.

Taylor was born in Indianapolis, Ind. in 1878, a time when bicycles and horses were the most common forms of transportation, and thousands attended cycling races in huge velodromes.

As a child, he was taken in and tutored by a wealthy white family who had a child near his age. Since that child had a bike, the family gave Taylor one too.

“He learned to ride. He didn’t think of racism until he tried to train at the YMCA and was turned away,” said Kranish.

Taylor was lucky to have a mentor, “Birdie” Munger, a world champion racer who owned a bike manufacturing company near a bike shop where Taylor worked.

Munger heard that Worcester would be a more favorable place for Taylor and decided to move his company -and Taylor- there.

According to Kranish, Taylor said, “One day I am going to return to Indianapolis and Major Taylor is going to be the fastest man in the world.”

Taylor was welcomed at the Worcester YMCA, and said, according to Kranish, “‘I have found my home.”

Kranish added the “Worcester Telegram wrote a story about 50,000 witnessing Taylor race. They might have exaggerated, but maybe not.”

In 1895, on a Munger bike, Taylor beat champion Eddie “Cannon” Bald in a half-mile sprint held in Madison Square Garden. He went on to complete a grueling 6-day race that counted total laps completed. Many dropped out. He finished the race.

Through Munger, Taylor met Arthur Zimmerman, who in 1895 wrote a training manual for cycling.

“Taylor became a student of nutrition and training. He trained religiously at the Y and kept his weight within an ounce of his optimum,” said Kranish.

Taylor went on to win races and set records throughout the world.

But all was not easy in Worcester. Kranish described a big Ku Klux Klan rally at Worcester’s Mechanic Hall. Racism was present throughout Taylor’s life.

The end of his life was not good either. Taylor lost his wealth through bad investments, the stock market crash, and generosity to others. His wife and daughter had left him. In 1932, he died in Chicago and was first buried in a pauper’s grave.

Sixteen years later, a group called the Bicycle Racing Stars of the Nineteenth Century asked Frank Schwinn, owner of Schwinn Bicycle Company, for a contribution towards the cost of exhuming and reburying Taylor. He was moved from a pauper’s to a marked grave in Chicago’s Mt. Glenwood cemetery.

To learn more about the Major Taylor Association, visit www.majortaylorassociation.org.

For more information on Kranish and his book, visit www.michaelkranish.com.