By Matt Robinson

Contributing Writer

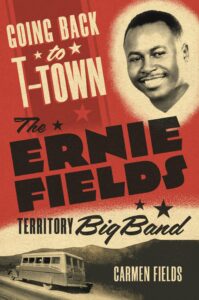

BOSTON – As a long-time journalist, Carmen Fields has told the story of many people’s lives. But the most personal story she has told is her father’s, the subject of her recent book, “Going Back to T-Town: The Ernie Fields Territory Big Band.”

In the 1930s, Tulsa, Oklahoma was still recovering from the aftermath of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, which had severely damaged its African-American community and the sense of safety in the city.

While many of the businesses that had once made up what was known as Black Wall Street were still in shambles, some African-Americans were able to find a way up and out.

One of these was musician and bandleader Ernie Fields.

A touring musician

Though he had moved to Tulsa in 1924 after graduating from Tuskegee University, Ernie Fields soon began touring far and wide. Along the way, he met such musical legends as country music king Bob Wills and recording impresario John Hammond. With the help of these and other devoted fans, Fields was able to write a story unlike most other artists of his time—that of an African-American bandleader who toured not only northern states but also the Jim Crow South.

As Ernie’s story is such a profound one, it deserved a qualified and experienced storyteller to share it. In “Going Back to T-Town,” Carmen Fields discusses her father as both public entertainer and private family man and shows how the lessons of the road educated her life at home (and vice versa). Along the way, she introduces readers to some of the great jazz men who played with and for her father, such as pianist Ernie Freeman, guitarist Rene Hall, saxophonist Plas Johnson, and drummers Earl Palmer and Roy Milton. She also discusses what life on the road was like for an African-American artist in that era.

Deep background in journalism

Much of her father’s story is based on a bus. So too is Carmen’s early journalism career, as she was part of the Boston Globe team that won the 1975 Pulitzer Prize for public service for its coverage of school desegregation and bussing in Boston. Her father was a pioneer who broke new ground in terms of where he appeared. Carmen has also, as the first African-American anchor on WGBH’s popular “Ten O’Clock News” broadcast and the creator and host of the public affairs program “Higher Ground” on WHDH. A graduate of Boston University’s master’s program in broadcast journalism, Carmen has also served as a journalism fellow at Harvard’s Nieman Foundation and assistant professor of journalism at Northeastern University.

When asked how she began her reporting career, Carmen recalled creating a newspaper in Tulsa at the age of nine.

“I collected neighborhood stories and placed the finished sheets in the mailboxes of my neighbors,” she explained, using mid-twentieth-century tools like typewriters and carbon paper. “The journalism flame was ignited by my seventh grade English teacher who had a segment on journalism in her lesson plan,” she explained.

First taste of television

After working on the school newspapers in junior and senior high school, Carmen majored in journalism at Lincoln University—an Historically Black College/University in Missouri. It was there that she got her first taste of television.

“I had an internship at the CBS affiliate station in Jefferson City, Missouri,” she explained. “That was why I decided to pursue broadcast journalism in grad school at BU.”

Though she focused on broadcast work, Carmen’s first job after graduating with her master’s degree was back in print, but at no less a place than the Boston Globe. After eight years there, Carmen moved again to broadcast. As often happens, she ended up in the right place at the right time.

“I was enlisted to fill in for an ill host of ‘Higher Ground’ for a few weeks on WHDH-TV,” she recalled when asked how she came to her own show. “The host recovered but never returned to the show, so I’ve remained as producer and host for over 20 years.”

Though she saw the costs of segregation at home and at work, Carmen admitted that she did not relate the two for some time. She also did not consider telling her father’s story for a long time either.

“Even as I was covering Boston’s school desegregation issues,” she said, “I did not connect that to what my father experienced in his professional career.”

The fact that she was often only one of a few African-American reporters at the various media outlets she served did not make Carmen think of her father’s story. “My Globe experience was a somewhat lonely experience because there were so few African-American staff members,” she maintained. “But my father had the support and close relations with the members of his orchestra who traveled from city to city on the band bus.”

Despite the relative lack of support, Carmen made her way in the world and was eventually ready to look back at her own story. Along the way, she learned a great deal about her family and herself.

Musical family

“I learned that my father (the youngest of six children) was not the only one in his family who was musically inclined,” she offered by way of example. “His older brothers and sisters were musical and gave him lessons on piano and sometimes performed with their minister father. One of his brothers was a sergeant bugler in World War I.”

Not only was the Fields family home filled with music, but the house was often a welcome stop for musicians who were passing through.

“Their home was where the famed Black choir director Eva Jessye stayed when she traveled to Black communities giving music lessons,” Carmen mentioned. “She also gave my father some piano training and always encouraged him to sing.”

While Ernie was undeniably talented, he would have been far less popular and progressive had it not been for the support of more established musical masters like Wills and Hammond. They helped open doors not only at various venues that other African-American performers might not have been allowed in but also at recording studios.

“My father’s opportunity to record is thanks in large part to his discovery by John Hammond,” Carmen said gratefully, mentioning how Hammond introduced her father to orchestra manager Willard Alexander. “Recordings and radio play made it possible to gain more recognition inside and outside his prescribed territory. And it helped keep him on par with other contemporary artists like Count Basie and Duke Ellington.”

This enhanced popularity, in turn, helped Fields recruit more popular players for his group, which increased audiences and made his band even more popular.

Among the talented musicians that were inspired by Ernie is Carmen’s brother Ernie Jr.

The next generation

“He took the lessons from his work with our dad’s orchestra to a higher plane,” Carmen attested. “Unlike my father, he was not as intent on keeping is name up in lights. He just wanted to toot his horn!”

Working with his father’s arranger, Rene Hall, the younger Ernie Fields was also able to access people and places that others did not. Also like his father, Ernie Jr. has used that access to support other artists. He has contracted musicians for recording sessions and for broadcasts that have included “The Voice,” “American Idol” and “PBS at the White House” and a popular music education program called “Jazz in Schools” that has reached over 20,000 students in Los Angeles.

Her father’s legacy

While it is clear that both Carmen and her brother took more than musical cues from their father, she suggests that her father’s legacy offers other ideas as well.

“There are three major lessons I hope people who read the book will take away,” she said, citing her father’s musicianship, entrepreneurship, and dedication to family.

“His career spanned the eras of jazz, swing, blues, and rock and roll,” she noted. She credits her father’s willingness to change with the times and to play what the audience wanted instead of what he might prefer. In order to offer his audiences maximum enjoyment, Fields added dancers and other entertainers to his shows. This helped employ and engage even more artists who might not otherwise be heard.

And while he did all he could to please people when out on the road, Carmen maintained that the most important thing she learned from her father was the importance of home. “He was a devoted family man who loved being home when his work did not require him to be on the road,” she recalled. Without the scourges of alcohol or drugs that plagued so many other artists, Fields was able to educate his children and remain married to Carmen’s beloved mother for 67 years.

“He always praised the fact that she never grumbled about his life on the road,” Carmen recalls. “She accepted his profession without complaint.”

RELATED CONTENT:

Daughter pays tribute to former BU president John Silber’s legacy

Veteran Boston DJ has also chronicled the rock world as an author